Slovenia’s biggest international film festival comparable to some of Europe’s main film showcases features outstanding achievements in global cinematography and major festival prize-winners (Cannes, Rotterdam, Berlin, Amsterdam, Vienna, etc.).

Oedipus Rex (Edipo re)

By: Pier Paolo Pasolini. 1967

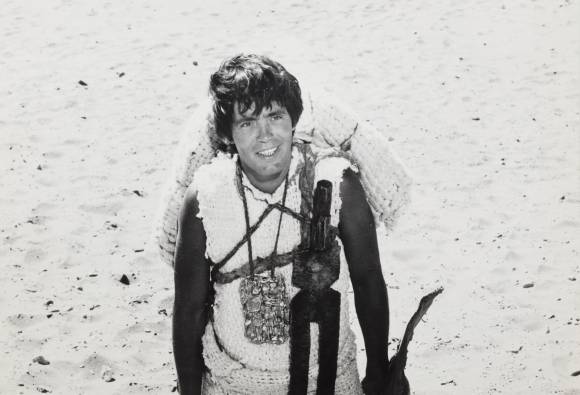

“The contrast between total innocence and the obligation to know; that is the thing in Sophocles that inspired me the most.” Pier Paolo Pasolini said another thing in reference to his Oedipus Rex: that in making it, he confronted his own anxiety, his own Oedipus complex, as formulated by Sigmund Freud. This is implied in the prologue and the epilogue, which bookend his re-working of Sophocles’ tragedy. The first scene shows a milestone that indicates the road to Thebes, and then the scene moves to what is recognizable as Bologna (Pasolini’s place of birth) – the midwife lifts a baby towards the light and the mother (Silvana Mangano who also plays Iocasta) breast-feeds the baby on a lawn while the father, a young officer (the profession of Pasolini’s father), resents his son stealing his wife’s love. In the epilogue, the blinded and aged Oedipus (Franco Citti), accompanied by young Angelo (Ninetto Davoli), returns to Bologna where Pasolini went to university.

Sophocles’ tragedy begins at the time the prophecy has already been fulfilled, when Oedipus has killed Laius, the King of Thebes and his biological father, and married the widowed Queen Iocasta, his biological mother. However, he discovers the truth gradually, through flashbacks or dialogues with other characters. Conversely, Pasolini employs no suspense because the story is told linearly and with minimal use of language, in a primordial silence inhabited by noises, murmurs and screams, to the accompaniment of age-old songs and musical rhythms. Whilst this already evokes a nonhistorical atmosphere, ahistoricism is all the more vividly conveyed by the desert landscape (the film was shot in Morocco), fictional costumes and even more bizarre weapons.

According to philosopher Clément Rosset, Oedipus is a classic example of prophetic illusion, when a man causes his own ruin by seeking to prevent it. Things are somewhat different with Pasolini. Oedipus learns about his own fate at the very beginning yet struggles against this knowledge, being unable to accept it and refusing to acknowledge the evil inside him. Oedipus refuses to accept his fate as this would mean admitting one’s own guilt. He is left with two choices, either opting for mindless violence so as to eliminate everything that reminds him of his destiny – he kills King Laius for no acceptable reason, merely out of the royal conceitedness he carries inside him – or senseless hoarding of privileges accorded to him by his fate; even his relationship with Iocasta is marked by possessiveness unwilling to forego sexual pleasures even when aware of the fact that the union is incestuous.

Insofar as Oedipus’ destiny can ‘even’ be said to be human, Pasolini imposes a limitation on it: as Oedipus represents the Western, dominant humanity, Pasolini links him to the Third World as the symbol of people sacrificed for the supremacy of the caste knowledgeable about “historical destiny”.

Oedipus Rex (Edipo re)

5'50 EUR

5% discount on online purchases cd-cc.si

On Mt. Olympus Festival

" width="580" height="395">

On Mt. Olympus Festival

" width="580" height="395">