Art Critics' Choice Series - Artist Presentation Series selected by the Slovenian Art Critics Association

Critic: Živa Kleindienst

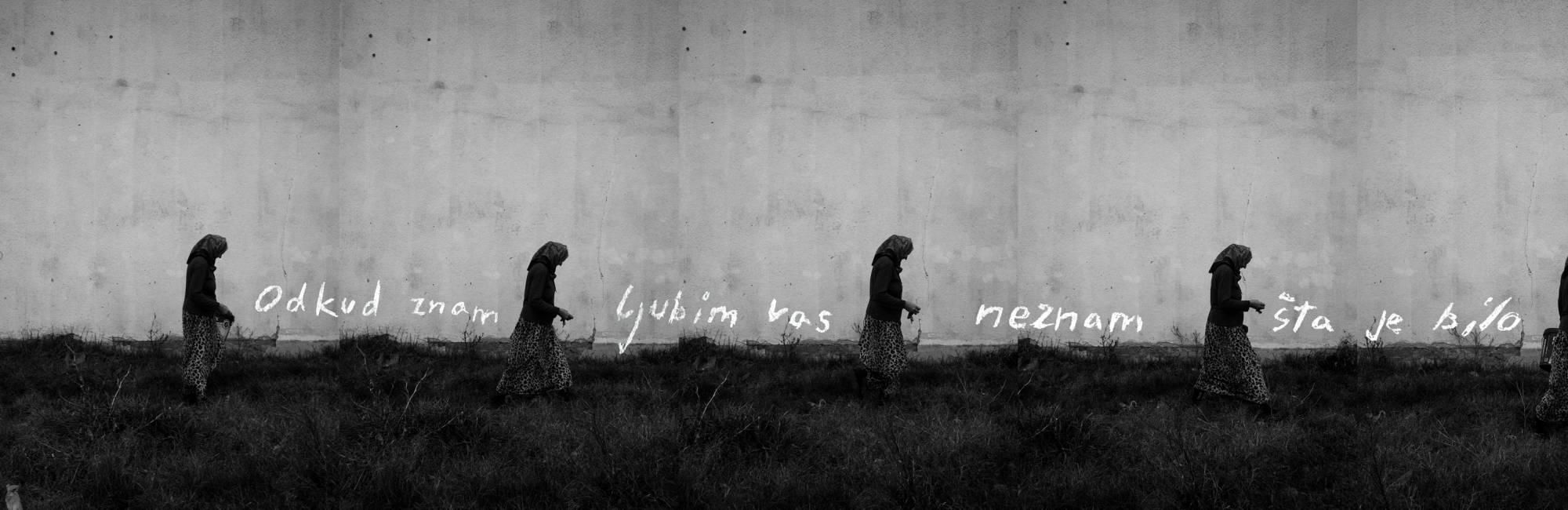

Jošt Franko: Odkud znam. Ljubim vas. Ne znam, šta je bilo.*

Take a virtual walk through the exhibition, from 27. Jan exhibition reopens.

*How am I to know. I love you. I don’t know what's happened.

Another person’s misfortune is a widespread motif in engaged photography and visual art. In the worlds of documentary, press and (also) art photography, questions are thus repeatedly raised about the ethics and decency of photographers in relation to their subjects, that is, people whose stories are made public by their works. Documenting or representing human misery can easily degenerate into media or artistic aesthetisation of social problems, whilst turning the subjects of these narratives into objects. Or, in plain terms, photographers or artists can boost their careers at the expense of other people’s misery, while leaving their subjects/objects caught in the clutches of their own adversity. That is why in different conflict zones photographers or artists are in a privileged position, and excluded from the situation, as they can, generally, choose to enter or leave freely, whereas the subjects/objects of their artworks usually do not have that option.

In Regarding the Pain of Others, philosopher and publicist Susan Sontag discusses, among other things, the apathy of the modern consumers of media content, who, due to the huge quantities of absorbed material, become more and more impassive and indifferent to the images of trauma and atrocities poured into their homes via the visual culture. Sontag also notes that, despite its overabundance, the visual image affects a spectator much more directly than, for example, a text will – although, in principle, words are (known to be) much more descriptive and explicit. Regardless of all these misgivings, discourse on social injustice and abuse in the public sphere is an indispensable and urgent necessity.

Considering that mass media devote less and less attention to unpleasant and complex issues, subjects of marginal interest are thus often raised by various alternative domains, including art. While here – in comparison to mass media – such narratives reach and address a much smaller circle of people, significantly greater freedom of artistic expression and creativity can nevertheless be exercised. In the absence of political or market pressures in treating particular social phenomena, the language of (engaged) art can indulge in an approach that is much more honest, consistent, contemplative, critical and complex.

Photographer and artist Jošt Franko is well aware of this fact and, as a result, consciously opts for a subtle and complex treatment of various social phenomena, including war and its far-reaching consequences. These repercussions often manifest themselves in tectonic economic, political, and demographic shifts, as well as in the resilient ideological, ethnic or religious disputes that survive the war basically intact. Franko focuses on the (too) quickly forgotten stories of Bosnia and Herzegovina, a country still coping with the aftermath of the bloody civil war whose end in 1995 did little to alleviate the situation of countless people continuing to bear, to this very day, the consequences on various levels of their daily lives.

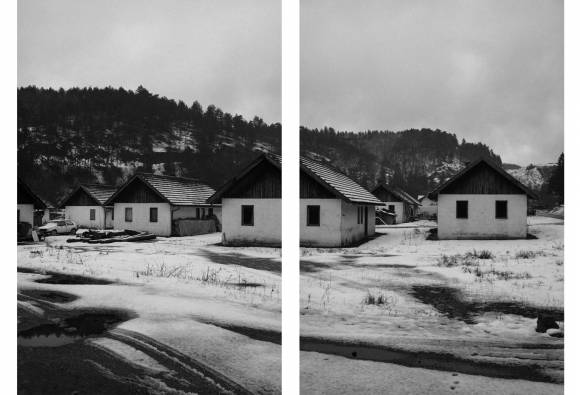

Today, more than twenty years after the war's end, there are still thousands of internally displaced persons in BiH, living in squalid conditions and with no socio-economic or legal status to speak of. While unable to return home because their former places of residence fell outside the new ethnic demarcation, their 'temporary' shelters lack the basic conditions for a dignified life. These people, coming from both entities of an ethnically divided country, are thus condemned to live below the poverty line and beyond civil rights. The authorities of both entities, however, simply ignore this problem with equal degree of obduracy.

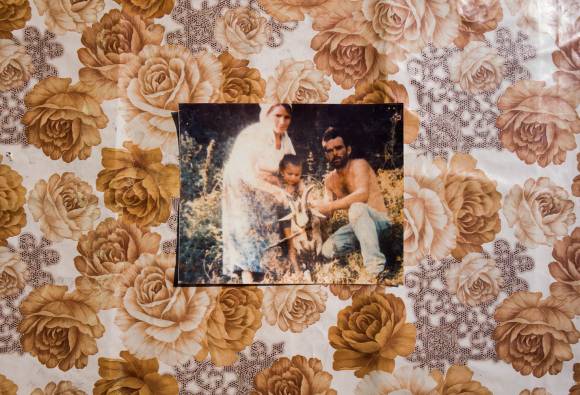

Franko has therefore brought into our living rooms, or displayed on gallery walls, these long-forgotten but still vividly present stories of long-term refugees in their own country. However, his method was not one of mere documentary reporting, but a non-linear representation of fragments of these complex phenomena. Perceiving photography and moving image as sociological categories, he always grounds his projects in subject matter, thereupon adjusting form and method of implementation in line with the addressed theme. In following this method, he gives a wide berth to any kind of illustration. On the contrary, he constructs distinctly metaphorical visual narratives based on the principle of 'pars pro toto'. He deals with particular personal stories of real people and, in the process, creates alternative micro-histories of sorts, histories ordinarily excluded from the prevalent media and public discourse – and therefore invisible. To this end, he avails himself of complete visual reduction, thus avoiding formulaic representations of misery.

One might suggest that his research and working methods bear a slight resemblance to the approach of Alfredo Jaar, an artist who, in his infamous Rwanda project from 1994, immediately after the end of this brutal conflict, followed a course that resisted the spectacle of action images and first-hand reports. Instead of photographs of the immediate aftermath of violence – at a time when dead bodies were still piled up on the ground – he created a small series of carefully selected pictures depicting this (invisible) violence in some sort of photographic and design vignettes. If with his series of prints, The Disasters of War (1810–1820), painter Francisco Goya sought to shock the public with explicit scenes of wartime violence against civilians, and succeeded in achieving this in an era preceding the development of mass visual culture, Jaar surmised that in the Information Age such a direct address would quickly become ineffective. We have grown all too accustomed to violence in remote areas, which we consume through mediated images, and our amnesia – like a self-defence mechanism against trauma – is swift. That is why the artist decided to address his viewership with a handful of select symbols, which, with only a few strokes, succeed in conveying the gist of the story and perhaps touching a spectator’s sensibilities.

Completely abandoning the principles of documentary photography and linear visual narrative, Franko’s latest works – realised consistently and continuously mainly over the past two years – stem from a similar concept. In this day and age, the classic documentary approach would most likely not have worked – given that, to most people, the Bosnian war is a resolved matter from the 1990s. It would also not be able to override the impression created by the brutal images of the bloodshed that took place between 1992 and 1995 – considering that due to the accessibility of battlefields the civil war in BiH was one of the most explicitly documented conflicts in recent history, and consequently provided many masters of modern warfare photo-safari with an opportunity to polish their skills. On the other hand, Franko aims to convey to the public the very silence and void left in its wake by the maelstrom of war. Particularly horrifying are the normalcy of the pictured situations and the resignation of people to their inevitable fate. And it is the people that are placed at the forefront of Franko’s work. The people with first-hand experience of the long-standing grey zone governing an administratively, politically and ethnically segregated country, a country whose grossly ineffective government tolerates rampant corruption and fuels unprocessed collective trauma.

Thus, people are at the heart of Franko's images, people whose mien is imprinted with the trauma of helplessness, loss, marginalisation, and homesickness. Many of the refugees he encountered, and with whom he communicated over longer periods of time, are still living in temporary housing, their minds wholly taken up by reminiscences, trying to cope with the past and the present, yet unable to think about the future. However, it is extremely difficult to visualise all these situations and phenomena, as an image will not suffice to fully reflect their overall subjective experience. How is a photographer, filmmaker or artist to portray the fate of people affected first by a devastating war, dispossessed of their homes and property, and then deprived of the opportunity to build a sound foundation for a dignified life by the processes of a brutal transition to neoliberal society? Franko uses fragments of their stories to construct a lapidary narrative that seeks to reach out to the spectator, not with the aim of pitying the plight and misfortune of people from distant areas, but of primarily encouraging reflection on the enduring repercussions of radical acts that lead to conflict. All this can happen – and has happened – anywhere.

Miha Colner

Jošt Franko: Odkud znam. Ljubim vas. Ne znam, šta je bilo.*

Vstop prost

Jošt Franko (1993) has been practising documentary and art photography over a number of years and has achieved both national and international recognition. Over the recent years, Franko has created several high-profile series and works, and has regularly exhibited at various photo/art showcases and festivals (New York Photo Festival, New York; Format Festival, Derby; Finnish Museum of Photography, Helsinki; Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova +MSUM, Ljubljana), while his photos have appeared in distinguished print and online media, including The New Yorker, TIME Magazine, Newsweek, The Washington Post, Le Monde, and Delo. Franko lives and works in Ljubljana.

Art historian Miha Colner (1978) is a curator at GBJ – Božidar Jakac Art Museum in Kostanjevica na Krki. He is also active as a lecturer and publicist, specialising in the fields of photography, graphic arts, moving image and various forms of (new) media art. Between 2017 and 2020, he curated the programme of the Švicarija Creative Centre, an arts venue managed by MGLC – International Centre of Graphic Arts, Ljubljana. He worked as a curator, between 2006 and 2016, at the Photon – Centre for Contemporary Photography in Ljubljana. Since 2005, he has been publishing articles in newspapers, magazines, and professional publications, as well as posting them in his blog. He lives and works in Ljubljana and Kostanjevica na Krki.